Performance-Aware Programming & Python: Optimizing Euclidean Distance Calculation

Introduction

Performance-aware programming is the practice of writing code with an understanding of how it executes on the underlying hardware. While Python is known for its ease of use and readability, it is often criticized for being slow compared to lower-level languages like C. However, with the right optimization techniques, Python programs can be significantly accelerated.

In this blog post, we will explore CPU optimizations in Python and C by optimizing a simple but computationally expensive function: calculating the Euclidean distance between two matrices. The goal is to show how performance bottlenecks arise and how we can systematically improve execution time using different optimization strategies.

Example to Improve: Euclidean Distance Computation

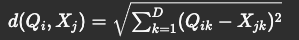

The Euclidean distance between two matrices, Q (M x D) and X (N x D), is a fundamental operation in machine learning and data science applications. Given:

- Q: A matrix of shape (M, D)

- X: A matrix of shape (N, D)

The Euclidean distance between every pair of rows from Q and X is computed as:

I will start by a basic naive python implementation:

import numpy as np

from math import sqrt

def euclidean_distance(Q: np.ndarray, X: np.ndarray) -> list[list[float]]:

"""

Compute the Euclidean distance between two matrices in a naive way.

Pure python implementation

Arguments:

Q -- A matrix of shape (M, D)

X -- A matrix of shape (N, D)

Returns: A matrix of shape (M, N) where each element (i, j) is the Euclidean distance between Q[i] and X[j]

"""

M, D = len(Q), len(Q[0]) # Q has M rows, D features

N = len(X) # X has N rows, D features

# Initialize distance matrix (M x N)

distances = [[0.0 for _ in range(N)] for _ in range(M)]

for i in range(M): # Iterate over each query vector

for j in range(N): # Iterate over each dataset vector

dist = 0.0

for k in range(D): # Compute squared distance

diff = Q[i][k] - X[j][k]

dist += diff * diff # Squaring each difference

distances[i][j] = sqrt(dist) # Compute final Euclidean distance

return distances

Waste: Understanding Python’s CPU Overhead

A CPU executes a sequence of instructions that perform computations. For Euclidean distance calculations, relevant instructions include:

Load: Fetching matrix values from memory.

- Subtract: Computing the difference between elements.

- Multiply: Squaring the differences.

- Sum: Accumulating the squared differences.

- Square Root: Finalizing the Euclidean distance calculation.

In an optimized language like C, these operations translate directly into efficient machine instructions. However, in Python, the execution path is far more complex. Example of x86_64 architecture:

int a = 0;

int b = 2;

a+=b;

—-----------------------------

mov eax, [var1] ; Load var1 into eax

mov ebx, [var2] ; Load var2 into ebx

add eax, ebx ; Add eax with ebx; store in eax

Python Execution: From Function Call to Machine Code

When executing a function in Python, the following steps occur:

- Python Function Call: The interpreter receives the function call.

- Python Interpreter Execution: The function is parsed and converted into bytecode.

- Bytecode Interpretation: CPython reads and interprets the bytecode.

- Assembler and Machine Code Execution: The CPU eventually processes low-level instructions derived from Python’s high-level operations.

Each of these steps introduces overhead, making Python significantly slower than compiled languages.

Unnecessary CPU cycles in Python

Python wastes CPU cycles with operations unrelated to actual Euclidean distance computation, such as:

- Dynamic Type Checking: Every operation involves type checks.

- Reference Counting for Memory Management: Objects are tracked, leading to frequent memory overhead.

- Interpreter Overhead: The Python runtime manages function calls, loops, and memory allocation dynamically.

Because of these inefficiencies, raw Python implementations of mathematical computations can be orders of magnitude slower than optimized C or NumPy implementations.

Example of disassembled python code using the dis module in the euclidean_distance function:

from dis import dis;

dis(naive_euclidean_distance)

24 266 LOAD_FAST 0 (Q) // Push to stack

268 LOAD_FAST 5 (i) // Push to stack

270 BINARY_SUBSCR // Pop two items from the stack, subscript them (Q[i]), and push the result

280 LOAD_FAST 8 (k) // Push to stack

282 BINARY_SUBSCR // Pop two items from the stack, subscript them (Q[i][k]), and push the result

292 LOAD_FAST 1 (X) // Push to stack

294 LOAD_FAST 6 (j) // Push to stack

296 BINARY_SUBSCR // Pop two items from the stack, subscript them (X[j]), and push the result

306 LOAD_FAST 8 (k) // Push to stack

308 BINARY_SUBSCR // Pop two items from the stack, subscript them (X[j][k]), and push the result

318 BINARY_OP 10 (-) // Pop two items from the stack, subtract them, and push the result

322 STORE_FAST 9 (diff) // Store the result in a variable

Using Numba for Just-In-Time Compilation

An alternative to rewriting in C is using Numba, a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler that translates Python code into optimized machine code using LLVM. Unlike CPython’s bytecode interpretation, Numba compiles the function at runtime and injects machine code into memory for execution.

A simple Numba-optimized implementation:

import numpy as np

import math

from numba import njit

@njit

def euclidean_distance(Q: np.ndarray, X: np.ndarray) -> list[list[float]]:

"""Computes Euclidean distance using a cache-friendly approach in pure Python"""

M = len(Q)

N = len(X)

D = len(Q[0])

Q_sq = [sum([q[d] ** 2 for d in range(D)]) for q in Q]

X_sq = [sum([x[d] ** 2 for d in range(D)]) for x in X]

distances = [[0.0] * N for _ in range(M)]

# Transpose X for better cache locality

X_T = [[X[n][d] for n in range(N)] for d in range(D)]

for i in range(M):

for j in range(N):

dot_product = sum([Q[i][d] * X_T[d][j] for d in range(D)])

distances[i][j] = math.sqrt(Q_sq[i] - 2 * dot_product + X_sq[j])

return distances

Why Numba Runs Faster?

- JIT Compilation: Translates Python functions into fast machine code at runtime.

- LLVM Optimization: Uses LLVM to optimize loops and memory access.

- Bypasses CPython Overhead: Avoids bytecode interpretation, reducing waste.

Minimal Code Changes: Requires only a decorator (@jit) to accelerate performance.

Using a C shared object from ctypes

To overcome Python’s overhead, we can implement the same Euclidean distance function in C. Unlike Python, C is a compiled language that translates directly to efficient machine code, avoiding the performance bottlenecks introduced by Python’s dynamic nature.

A simple C implementation of Euclidean distance computation:

#include <math.h>

// Function to compute pairwise Euclidean distance

void euclidean_distance(float* Q, float* X, float* distances, int M, int N, int D) {

// Iterate over all pairs of points

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

float sum_sq = 0.0;

for (int k = 0; k < D; k++) {

// We access Q and X in a row-major order by computing the index

// as i * D + k and j * D + k respectively.

float diff = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

sum_sq += diff * diff;

}

distances[i * N + j] = sqrt(sum_sq);

}

}

}

In order to call it from python we can use the ctypes module:

import ctypes

import numpy as np

# Load the compiled C shared library

lib = ctypes.CDLL("./naive.so") # Use ".dll" on Windows

# Define function prototype: void euclidean_distance(float*, float*, float*, int, int, int)

lib.euclidean_distance.argtypes = [

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float), # Q

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float), # X

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float), # D_matrix

ctypes.c_int, # M

ctypes.c_int, # N

ctypes.c_int # D

]

def euclidean_distance(Q: np.ndarray, X: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""Call the C function for Euclidean distance computation"""

M, D = len(Q), len(Q[0])

N = len(X)

# Flatten NumPy arrays to 1D C-compatible arrays

q_flat = Q.flatten()

x_flat = X.flatten()

distances = np.zeros((M, N), dtype=np.float32)

# Convert to C pointers

q_ptr = q_flat.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float))

x_ptr = x_flat.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float))

d_ptr = distances.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float))

# Call the C function

lib.euclidean_distance(q_ptr, x_ptr, d_ptr, M, N, D)

return distances

- No Interpreter Overhead: The compiled C code runs directly on the CPU.

- Efficient Memory Management: C operates on raw arrays with minimal overhead.

Instruction-Level Parallelism

Modern CPUs have multiple execution pipelines, allowing them to process multiple instructions in parallel. However, naive implementations do not fully utilize this capability.

Challenges in Parallel Execution

- Pipeline Dependency: The instruction pipeline can only compute the next value of the sum if the current one has been completed.

- Missed Opportunities for Optimization: The sum operation does not take advantage of the commutative property - the order of addition does not matter for the addition operation.

Generated instructions in Arm A64 (M1 chip) for the inner loop of the C implementation:

0000000000003ee4 ldr x8, [sp, #0x38]

0000000000003ee8 ldr w9, [sp, #0x18]

0000000000003eec ldr w10, [sp, #0x1c]

0000000000003ef0 mul w9, w9, w10

0000000000003ef4 ldr w10, [sp, #0xc]

0000000000003ef8 add w9, w9, w10

0000000000003efc ldr s0, [x8, w9, sxtw #2]

0000000000003f00 ldr x8, [sp, #0x30]

0000000000003f04 ldr w9, [sp, #0x14]

0000000000003f08 ldr w10, [sp, #0x1c]

0000000000003f0c mul w9, w9, w10

0000000000003f10 ldr w10, [sp, #0xc]

0000000000003f14 add w9, w9, w10

0000000000003f18 ldr s1, [x8, w9, sxtw #2]

0000000000003f1c fsub s0, s0, s1

0000000000003f20 str s0, [sp, #0x8]

0000000000003f24 ldr s0, [sp, #0x8]

0000000000003f28 ldr s1, [sp, #0x8]

0000000000003f2c ldr s2, [sp, #0x10]

0000000000003f30 fmadd s0, s0, s1, s2 // -> Only one fused multiply-add instruction per cycle

0000000000003f34 str s0, [sp, #0x10]

0000000000003f38 b 0x3f3c

0000000000003f3c ldr w8, [sp, #0xc]

0000000000003f40 add w8, w8, #0x1

0000000000003f44 str w8, [sp, #0xc]

0000000000003f48 b 0x3ecc

0000000000003f4c ldr s0, [sp, #0x10]

0000000000003f50 fcvt d0, s0

0000000000003f54 fsqrt d0, d0

Loop unrolling

By unrolling the loop, we can increase the number of instructions executed per iteration, allowing the CPU to better utilize its execution pipelines.

#include <math.h>

#define UNROLL_FACTOR 4

void euclidean_distance(float* Q, float* X, float* distances, int M, int N, int D) {

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

float sum_sq = 0.0;

int k = 0;

// Unrolled loop

for (; k <= D - UNROLL_FACTOR; k += UNROLL_FACTOR) {

float diff1 = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

float diff2 = Q[i * D + k + 1] - X[j * D + k + 1];

float diff3 = Q[i * D + k + 2] - X[j * D + k + 2];

float diff4 = Q[i * D + k + 3] - X[j * D + k + 3];

sum_sq += diff1 * diff1 + diff2 * diff2 + diff3 * diff3 + diff4 * diff4;

}

// Handle remaining elements

for (; k < D; k++) {

float diff = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

sum_sq += diff * diff;

}

distances[i * N + j] = sqrt(sum_sq);

}

}

}

Let’s take a look now at the generated instructions for the inner loop:

0000000000003e74 str s0, [sp, #0xc] // Storing in #0xc diff4.

0000000000003e78 ldr s0, [sp, #0x18] // loading diff2 into s0

0000000000003e7c ldr s1, [sp, #0x18] // loading diff2 into s1

0000000000003e80 ldr s2, [sp, #0x14] // loading diff1 into s2

0000000000003e84 ldr s3, [sp, #0x14] // loading diff1 into s3

0000000000003e88 fmul s2, s2, s3 // Multiplying diff1 * diff1

0000000000003e8c fmadd s2, s0, s1, s2 // Adding diff2 * diff2 to the previous result

0000000000003e90 ldr s0, [sp, #0x10] // loading diff3 into s0

0000000000003e94 ldr s1, [sp, #0x10] // loading diff3 into s1

0000000000003e98 fmadd s2, s0, s1, s2 // Adding diff3 * diff3 to the previous result

0000000000003e9c ldr s0, [sp, #0xc] // loading diff4 into s0

0000000000003ea0 ldr s1, [sp, #0xc] // loading diff4 into s1

0000000000003ea4 fmadd s1, s0, s1, s2 // Adding diff4 * diff4 to the previous result

It now generates more instructions per iteration, allowing the CPU to better utilize its execution pipelines.

CPU Caching

Efficient memory access is crucial for high-performance computing. Modern CPUs rely on multi-level caches to speed up memory access, but poor memory access patterns can lead to frequent cache misses and slow down computation.

Understanding CPU Caches

- Cache Lines: Data from RAM is loaded into the CPU cache in blocks called cache lines, typically 64 bytes in size.

-

Cache Hierarchy: CPUs have multiple levels of cache (L1, L2, L3) that are much faster than RAM.

- L1 Cache (Fastest, Smallest)

- Size: Typically 32KB to 128KB per core

- Latency: ~3-5 CPU cycles

- L2 Cache (Larger, Slightly Slower)

- Size: Typically 256KB to 2MB per core

- Latency: ~10 CPU cycles

- L3 Cache (Largest, Shared Across Cores)

- Size: Typically 4MB to 64MB shared across all cores

- Latency: ~30-50 CPU cycles RAM (Slowest, Largest)

- Latency: ~100+ CPU cycles

- L1 Cache (Fastest, Smallest)

- Cache Locality: Accessing nearby memory locations increases the likelihood of cache hits.

- Cache Evictions:: When new data is loaded and there isn’t enough space in the cache, old data gets evicted.

Modern CPUs have hardware prefetchers that try to predict memory access patterns and load data into cache before it is needed. Efficient memory access should follow predictable patterns that align with cache prefetching. However, accessing data inefficiently can lead to performance issues:

To optimize performance:

Access Memory Sequentially: Iterating over contiguous memory locations minimizes cache misses. Structure Data for Locality: Store data in a way that maximizes reuse before eviction. Use Blocking Techniques: Process data in small blocks that fit within cache lines to reduce cache thrashing. By optimizing memory access patterns, we can significantly speed up our Euclidean distance computations and take full advantage of modern CPU architectures.

Our issue

In our Euclidean distance computation, we compute distances between rows of matrices Q (M × D) and X (N × D).

A naive implementation accesses X[j, k] repeatedly for each element in Q, which leads to poor cache utilization since not the entire X matrix migh fit in the cache.

Each iteration accesses a new row of X, which may cause cache eviction.

Fetching X[j, k] again requires reloading it from RAM, adding significant latency.

This leads to thrashing, where useful data is frequently replaced before it can be reused.

Solution: Blocking

void euclidean_distance(float* Q, float* X, float* distances, int M, int N, int D) {

for (int j_block = 0; j_block < N; j_block += B) { // Process X in blocks

int j_end = (j_block + B < N) ? (j_block + B) : N; // Ensure last block fits

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (int j = j_block; j < j_end; j++) { // Iterate within block

float sum_sq = 0.0;

int k = 0;

// Unrolled loop

for (; k <= D - UNROLL_FACTOR; k += UNROLL_FACTOR) {

float diff1 = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

float diff2 = Q[i * D + k + 1] - X[j * D + k + 1];

float diff3 = Q[i * D + k + 2] - X[j * D + k + 2];

float diff4 = Q[i * D + k + 3] - X[j * D + k + 3];

sum_sq += diff1 * diff1 + diff2 * diff2 + diff3 * diff3 + diff4 * diff4;

}

// Handle remaining elements

for (; k < D; k++) {

float diff = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

sum_sq += diff * diff;

}

distances[i * N + j] = sqrt(sum_sq);

}

}

}

}

Now we process X in blocks of size B, ensuring that each block fits within the cache. The next block will only start once the current block is finished being used for all elements in Q.

SIMD Vectorization

To further improve performance, we can use Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD), which allows multiple computations to be executed in parallel using special vector instructions.

Understanding CPU Registers

Registers are small, ultra-fast memory locations inside the processor that store:

- Operands and results of operations

- Memory addresses during execution

- Control information for execution flow

Types of registers include:

- General-purpose registers (store intermediate values)

- Control registers (manage execution state)

- Instruction pointer registers (track execution position)

- Flag registers (store condition codes)

SIMD: Processing Multiple Values at Once

Normally, if we wish to operate on multiple operands, we require separate instructions for each operation. SIMD allows a single instruction to perform the same operation on multiple values simultaneously by using larger registers(vector registers) designed for parallel execution. SIMD Extensions: NEON (ARM) and SSE (x86) Most modern CPUs include SIMD extensions:

- ARM (Apple M1, ARM64): Uses NEON instructions for vectorized computation.

- x86 (Intel, AMD): Uses the SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) and AVX (Advanced Vector Extensions) instruction sets:

- SSE2, SSE3, SSE4: Earlier SIMD instruction sets for floating-point and integer operations.

- AVX, AVX2: Wider registers (256-bit) for more parallelism.

- AVX-512: Newer CPUs support 512-bit registers for even higher throughput.

Leveraging SIMD for Euclidean Distance Computation

By using SIMD, we can:

- Load multiple floating-point values into a single register.

- Perform parallel operations on multiple data points in one instruction.

- Reduce loop iterations and instruction count, improving execution efficiency.

Using optimized libraries like NumPy (which internally uses SIMD) or writing explicit vectorized code with compiler intrinsics can drastically improve performance.

import numpy as np

def euclidean_distance(Q: np.ndarray, X: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Compute the Euclidean distance between two matrices using numpy.

Pure numpy implementation

Arguments:

Q -- A matrix of shape (M, D)

X -- A matrix of shape (N, D)

Returns: A matrix of shape (M, N) where each element (i, j) is the Euclidean distance between Q[i] and X[j]

"""

distances = np.linalg.norm(Q[:, None] - X, axis=2)

return distances

Vector intrinsics in C

When running on MACOS: The SSE intrinsics are not available on macOS, so we need to use the

sse2neon.hheader file to emulate the SSE intrinsics using NEON intrinsics.

Below we can see the optimized C implementation using SIMD intrinsics:

- Setting the sum vector to zero.

- Loading 4 elements at a time from Q and X.

- Subtracting the elements.

- Squaring the differences.

- Reducing the 4 floats to 1.

- Handling the remaining elements.

// SSE intrinsics

// 4 for SSE, 8 for AVX

#ifdef __x86_64__

#include <immintrin.h>

#else

#include "sse2neon.h"

#endif

// SIMD-optimized Euclidean distance function

void euclidean_distance(float* Q, float* X, float* distances, int M, int N, int D) {

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

__m128 sum_vec = _mm_setzero_ps(); // Initialize SIMD sum register to 0

int k;

int block_size = 4;

for (k = 0; k <= D - block_size; k += block_size) { // Process 4 elements at a time

__m128 q_vec = _mm_loadu_ps(&Q[i * D + k]);

__m128 x_vec = _mm_loadu_ps(&X[j * D + k]);

__m128 diff = _mm_sub_ps(q_vec, x_vec);

__m128 squared = _mm_mul_ps(diff, diff);

sum_vec = _mm_add_ps(sum_vec, squared);

}

// Horizontal sum of sum_vec (reduces 4 floats to 1)

__m128 temp = _mm_add_ps(sum_vec, _mm_movehl_ps(sum_vec, sum_vec));

temp = _mm_add_ss(temp, _mm_shuffle_ps(temp, temp, 1));

float sum = _mm_cvtss_f32(temp); // Extract final sum

// Handle remaining elements (if D is not a multiple of 4)

for (; k < D; k++) {

float diff = Q[i * D + k] - X[j * D + k];

sum += diff * diff;

}

// Store result in distance matrix

_mm_store_ss(&distances[i * N + j], _mm_sqrt_ps(temp));

}

}

}

Note the differences in the generated instructions for the inner loop:

0000000000003f34 dup.2d v1, v0[1]

0000000000003f38 fadd.4s v0, v0, v1

0000000000003f3c dup.4s v1, v0[1]

0000000000003f40 movi.2d v2, #0000000000000000 // Set v2 to 0 -> _mm_setzero_ps()

0000000000003f44 mov.s v2[0], v1[0]

0000000000003f48 fadd.4s v0, v0, v2

0000000000003f4c add x17, x14, x15

0000000000003f50 fsqrt.4s v0, v0 // Square root of the sum

0000000000003f54 str s0, [x2, x17, lsl #2]

0000000000003f58 add x14, x14, #0x1

0000000000003f5c add x16, x16, x12

0000000000003f60 cmp x14, x13

0000000000003f64 b.eq 0x3f0c

0000000000003f68 movi.2d v0, #0000000000000000

0000000000003f6c cmp w5, #0x4

0000000000003f70 b.lt 0x3f34 // Loop back

0000000000003f74 mov x17, #0x0

0000000000003f78 mov x3, x0

0000000000003f7c mov x6, x16

0000000000003f80 ldr q1, [x3], #0x10

0000000000003f84 ldr q2, [x6], #0x10

0000000000003f88 fsub.4s v1, v1, v2 // Subtract the elements -> _mm_sub_ps()

0000000000003f8c fmul.4s v1, v1, v1 // Square the differences -> _mm_mul_ps()

0000000000003f90 fadd.4s v0, v0, v1 // Add the squared differences -> _mm_add_ps()

0000000000003f94 add x17, x17, #0x4

0000000000003f98 cmp x17, x9

0000000000003f9c b.le 0x3f80

0000000000003fa0 b 0x3f34

Conclusions

Optimizing performance in Python requires an understanding of how the CPU processes instructions and accesses memory. While Python’s high-level nature makes it easy to use, it also introduces inefficiencies that can slow down execution. By applying techniques such as cache-friendly memory access, instruction-level parallelism, and SIMD vectorization, we can significantly improve performance.

In this post, we demonstrated how to optimize Euclidean distance calculations using:

Efficient memory access patterns to reduce cache misses.

- Blocking techniques to improve cache locality.

- Loop unrolling to increase instruction-level parallelism.

- SIMD instructions to execute multiple operations in parallel.

For high-performance applications, leveraging tools like NumPy, Numba, and C extensions can further accelerate computations. By being mindful of CPU architecture and optimizing at the hardware level, we can push Python’s performance closer to that of lower-level languages like C.

With the right optimizations, Python can be an excellent choice for computationally intensive tasks while maintaining its readability and ease of use.